The magic flute

- garethsprogblog

- Jan 31, 2015

- 6 min read

Back in 2015, the lack of availability of albums by progressivo Italiano band Jumbo forced me to buy a download of DNA, the first of their two classic albums. I’d seen vocalist-guitarist-songwriter Alvaro Fella performing with Consorzio Acqua Potable at the Riviera Prog festival in Genova 2014 and despite my decision to miss the CAP set when I went off in search of food, the loose organisation meant that I actually caught a fair amount of their performance. Fella, at that time confined to a wheelchair, had been signing copies of Jumbo CDs all day but when I went to see if I could buy either DNA or Vietato ai Minori di 18 Anni? (Forbidden to Minors Under 18?) from one of the many diverse CD and record stalls, there were none available. Subsequent trips to Tuscany and the Veneto also failed to turn up copies.

DNA represents fairly basic RPI but it’s still quite enjoyable. Fella’s vocals might be something of an acquired taste – he has a distinctive theatrical style that has hints of Alex Harvey or Roger Chapman from Family and there’s not a great deal of variation in the keyboard with only organ and piano but like quite a lot of progressivo Italiano, there’s a hefty dose of flute in the styles of Ian Anderson and melodic early King Crimson. DNA was Jumbo’s first foray into a progressive sound but there’s still a weighty reminder of their past influences, including too much harmonica for my liking. However, Ed Ora Corri (And now you have to run) which is the second part of the three-part Suite per il Sig K., a composition that makes up side one of the original vinyl LP (a track that reflects a Kafka-like existence) is quite spacey and seems to have been at least partially inspired by Pink Floyd.

Jumbo albums DNA and Vietato ai Minori di 18 anni?

Considering the widespread employment of the instrument in Italian progressive rock, flute isn’t over prevalent in classic UK prog. No doubt due to their longevity, Jethro Tull are one of the bands that immediately spring to mind when you think of prog and flute, where Ian Anderson’s instrumental contributions are almost exclusively flute and acoustic guitar. His guitar parts don’t really provide much other than rhythm or chords for backing other instruments, including his flute, but I’d describe his main roles as songwriter, vocalist and guitarist. Almost all other prog flute is provided by band members who have a different primary role: Thijs van Leer plays keyboards; Andy Latimer plays guitar; Ian McDonald played saxophone and keyboards for King Crimson; Peter Gabriel is a vocalist.

I’ve seen Focus a few times in recent years and once in the 70s on the Mother Focus tour. Though van Leer is probably most easily recognised for his yodelling on Hocus Pocus, it’s his organ and flute work that helps to define the Focus sound (Jan Akkerman’s guitar is obviously key but that has been accurately replicated by Niels van der Steenhoven and, more recently, by Menno Gootjes.) Van Leer plays both instruments at the same time! The Camel track Supertwister from 1974’s Mirage is allegedly named after Dutch band Supersister. I can believe this tale because the two groups toured together and the Camel song does sound rather like a Supersister composition, where flute was provided by Sacha van Geest. Latimer does play a fair amount of flute on early Camel albums (from Mirage to Rain Dances) but the incorporation of King Crimson woodwind-player Mel Collins into the band reduced Latimer’s flute playing role, especially for live performances, and when Collins ceased working with the band, which turned more commercial around the 80s, the flute all but disappeared. Peter Gabriel’s flute is predominantly used in pastoral-sounding passages; it’s delicate and sometimes seems to border on the faltering but comes to the fore in Firth of Fifth. It may seem contradictory but the instrument works perfectly well on the grittier, urban-like The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway and his first solo album Peter Gabriel (Car).

Thijs Van Leer's Introspection 2, the second of his classical flute albums

Ray Thomas of the Moody Blues was one of the only examples of a dedicated flautist within a band, though he also undertook some lead vocal duties and there were groups, like King Crimson, where multi-instrumentalists played saxophone, flute and keyboards. Dick Heckstall-Smith of Colosseum was a sax player who dabbled in a bit of flute but the best example of a classic British prog band where sax and flute alternate as lead instruments is Van der Graaf Generator. I think David Jackson stands apart in this respect; he’s a soloist on both instruments, heavily informed by Roland Kirk. The Jackson sax is undeniably an integral part of the VdGG sound between 1970 and 1972, 1975 and 1976 and for the reunion album Present in 2005 - partly through his innovative use of effects, but his flute is also sublime, floating in the calm before the inevitable full-on VdGG maelstrom.

Jimmy Hastings deserves a special mention. He was the go-to flautist for a wide variety of the so-called ‘Canterbury’ bands, most notably Caravan (where brother Pye plays guitar) but he also contributed to material as diverse as Bryan Ferry’s solo work and Chris Squire’s Fish out of Water. It’s his Canterbury connections that run the deepest, adding to the jazz feel of the genre and making important contributions to Hatfield and the North and National Health albums. Canterbury alumni Gong have also utilised sax/flute, originally played by Didier Malherbe and more recently by Theo Travis. Travis has recorded with Robert Fripp and has recorded and toured with Steven Wilson.

The idea of the ‘guest’ flautist in a band spreads to Steve Hackett who has utilised the talents of both his brother John and more recently Rob Townsend, though Townsend’s contribution has widened significantly from flute and saxophone to include keyboards and percussion on recent Steve Hackett tours. Flute is required for covering some of the early Genesis material but Hackett’s solo work from Voyage of the Acolyte (1975) to Momentum (1988) all feature flute, with the exceptions of Highly Strung (1983) and Till We Have Faces (1984).

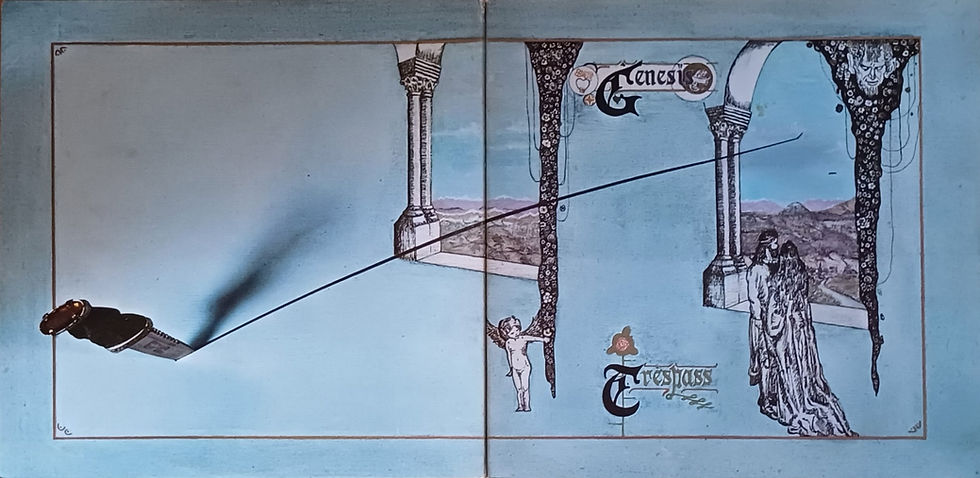

The overblowing that characterises a great deal of Ian Anderson’s flute for Jethro Tull was adopted by many nascent progressivo italiano bands who were shifting from Beat music to a blues-inflected progressive rock and this contrasts with the more melodic approach exemplified by the Ian McDonald-era King Crimson that seems to have influenced Mauro Pagani of PFM. It’s equally hard to believe that Peter Gabriel’s flute playing wasn’t an influence on Italian artists, where the popularity of Genesis was at that time greater than in the UK; Nursery Cryme (1971) reached no.4 in the Italian charts but didn’t chart in the UK until May 1974 when it peaked at no.39, and Foxtrot (1972) reached the top spot in Italy but only managed no.12 in the UK. It may be as a result of Italy’s musical heritage that a flautist is more likely to be involved in a rock band; both historically and currently there seem to be more groups with flute than without, very different from the 70’s scene in the UK.

Mauro Pagani of PFM

The presence of flute in a host of bands from other European countries, including those from former communist territories, is an indication of the instrument’s integration into the symphonic progressive rock palette. Đorđe Ilijin played keyboards and flute for Yugoslavia’s Tako, Attila Kollár of Hungary’s Solaris was primarily a flautist, though he did add other instrumentation (and ended up as the lead vocalist on 2019’s Nostradamus 2.0 – Returnity), and Hungarian multi-instrumentalist Yoel Schwarcz who founded the multi-national Continuum in Amsterdam in 1970 included flute in his array of instruments. The Netherlands is represented by Focus, Supersister and by Earth and Fire, where keyboard player Gerard Koerts occasionally played flute. The instrument was essential to the sound of France’s Pulsar, played by Roland Richard; Spain’s highly regarded Gotic used flute as a lead instrument; Norway’s Wobbler employ a guest flautist on a number of their releases which enhances their medieval sounding moments and Håkon Oftung, the multi-instrumentalist from fellow countrymen Jordsjø, creates a dark-prog-folk atmosphere with his flute; Sten Bergman added flute to Bo Hansson’s albums, enhancing the bucolic feel of the music; Änglagård’s Anna Holmgren played flute on their first two albums and by the time I managed to get to see them in 2014 she had added sax, Mellotron and balloons to her sonic armoury; even Tangerine Dream used real flute, played by the guest musician Thomas Keyserling on Electronic Meditation (1970), by Chris Franke and Udo Dennenberg on Alpha Centauri (1971), and by Steve Jolliffe when he joined for Cyclone in 1978.

Tangerine Dream and Edgar Froese solo albums provided some of the best examples of spine-chilling Mellotron flute, an entirely valid sound for bands without the real thing. It may be quite distinct from the woodwind instrument itself, but it is a great sound!

The examples listed above are plucked from artists represented by pieces of music that I own, so I’ve no doubt missed some important exponents. The list, however incomplete and however small a proportion of my collection is enough to indicate that my taste tends towards music that includes the broad sonic palette best associated with symphonic prog where, in my opinion, the flute finds a natural home. It is undoubtedly a prog instrument.

コメント